My Pyramid for moms

| When you are pregnant or breastfeeding, you have special nutritional needs. This section of MyPyramid.gov is designed just for you. It has advice you need to help you and your baby stay healthy. |

First — visit your health care provider if you haven’t already. Every pregnant woman needs to visit a health care provider regularly. He or she can make sure both you and your baby are healthy. Your provider can also prescribe a safe vitamin and mineral supplement, and anything else you may need.

First — visit your health care provider if you haven’t already. Every pregnant woman needs to visit a health care provider regularly. He or she can make sure both you and your baby are healthy. Your provider can also prescribe a safe vitamin and mineral supplement, and anything else you may need.

Next — get your own MyPyramid Plan for Moms. Your Plan will show you the foods and amounts that are right for you. Enter your information for a quick estimate of what and how much you need to eat.

Then — learn more by choosing a topic from the menu below. The “Sources of Information” will take you straight to the government’s best advice on pregnancy and breastfeeding.

How to Establish a Diet Plan

from wikiHow - The How to Manual That You Can Edit

Are you unsure of which diet plan is right for you? Stop putting off that diet because of indecision, and establish a suitable diet plan that you can follow. These are just a few in the LONG list of diets that you can choose from.

Steps

- Diet Drinks & Shakes: Though these can work for some people, they are not ideal for individuals with digestive problems. The weight loss is often very slow, but quite difficult to gain back.

- Low-Carb: If you don't want to exercise, stay away from these diets. The higher protein levels demand a certain degree of excerise if you want to achieve maximum results.

- Low-Fat: When followed correctly, these diets can produce good results. Beware: By cutting out ALL fat intake, your body will reap negative effects. Just as too much fat is a bad thing, too little fat is also a bad thing.

- Moderation: Simply put, eat less. Moderation plans enable the dieter to eat less, while still enjoying craved tastes. This plan is ideal for dieters with little will power.

- Grapefruit Diet: This plan is effective for speedy weight loss. While the kind of food available for eating is slim, the actual amount of food is excessive. If this plan is chosen, expect to eat great quantities of food and lose weight quickly, but to gain it back almost instantly.

- Metabolism-Speeding: The idea behind these diets is that if you combine certain foods, you will speed up your metabolism. These diets have not been proven effective. Most doctors believe that they work only as placebos.

- Exercise-Only: If exercise is the force that drives you, and you don't want to concern yourself with food, try increasing your exercise level.

- Encouragement Diets: These diets enable you to work with others to achieve your goals. They team exercise with moderation, and add a friendly dose encouragement that people can rely on. They are ideal for people who need to be "pushed" in order to go that extra mile. Weight Watchers and Jenny Craig are good examples of encouragement plans.

Tips

- Whatever your final decision is, realize your goals and do not make them unreachable.

- If you are a vegetarian who follow a low carb diet, then consume more eggs, cheeses, tofu and also eat only complex carbs. Source: Low Carb Vegetarian

Warnings

- The Grapefruit Diet is intended as a temporary plan. It is advisable to stay on this diet for no more than 14 days.

- The Grapefruit Diet Plan allows no more than 800 calories a day. It is a very strict diet plan for instant weight loss, BUT NOT a healthy diet. Your body is going to miss out some important nutrients not included in the diet. A balanced diet should consist of 4 food groups. With the grapefruit juice diet plan, it is cutting out a couple of the food groups. Source from: Grapefruit Diet

If you believe in yourself enough you will acheive your goals you should always have someone on hand who also wants to lose weight it will be easier and a friend that will support you is always good to have try it this plan really works.

if you want to lose weight don't lose it all at once lose it gradually as you know if you lose too much then you can gain what you have lost just reverse your first plan and it is as simple as that.

Related wikiHows

- How to Evaluate Your Eating Habits

- How to Keep to Your Diet

- How to Get the Most Effective Diet

- How to Diet Without the Myth of Fat Burning Foods

- How to Prevent Jet Lag With a Modified Diet

- How to Lose Weight With Juicing

- How to Sauté Vegetables

- How to Be an Earthy Girl

- How to Eat Small Portions During Meals

- How to Choose the Right Chewing Gum

Article provided by wikiHow, a wiki how-to manual. Please edit this article and find author credits at the original wikiHow article on How to Establish a Diet Plan. All content on wikiHow can be shared under a Creative Commons license.

Weight of the Nation

Weight of the Nation is designed to provide a forum to highlight progress in the prevention and control of obesity through policy and environmental strategies and is framed around four intervention settings: community, medical care, school, and workplace. Plenary and concurrent sessions will focus on strategies implemented in these settings that have lead to policy and environmental changes which may improve population-level health. A key feature of the conference is a move from didactic presentations to an emphasis on interactive discussion between plenary and concurrent session panelists, and the audience. Plenary sessions will present case studies on the use of policy and environmental strategies within certain settings (e.g., workplaces) and sectors (e.g., law or economics) while concurrent sessions will discuss specific issues within the setting context (e.g., strategies to leverage built-environment initiatives to increase physical activity in workplaces).

Weight of the Nation is designed to provide a forum to highlight progress in the prevention and control of obesity through policy and environmental strategies and is framed around four intervention settings: community, medical care, school, and workplace. Plenary and concurrent sessions will focus on strategies implemented in these settings that have lead to policy and environmental changes which may improve population-level health. A key feature of the conference is a move from didactic presentations to an emphasis on interactive discussion between plenary and concurrent session panelists, and the audience. Plenary sessions will present case studies on the use of policy and environmental strategies within certain settings (e.g., workplaces) and sectors (e.g., law or economics) while concurrent sessions will discuss specific issues within the setting context (e.g., strategies to leverage built-environment initiatives to increase physical activity in workplaces).The conference objectives are:

for more information

CDC:Definitions for Adults- obesity

For adults, overweight and obesity ranges are determined by using weight and height to calculate a number called the "body mass index" (BMI). BMI is used because, for most people, it correlates with their amount of body fat.

- An adult who has a BMI between 25 and 29.9 is considered overweight.

- An adult who has a BMI of 30 or higher is considered obese.

See the following table for an example.

| Height | Weight Range | BMI | Considered |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5’ 9" | 124 lbs or less | Below 18.5 | Underweight |

| 125 lbs to 168 lbs | 18.5 to 24.9 | Healthy weight | |

| 169 lbs to 202 lbs | 25.0 to 29.9 | Overweight | |

| 203 lbs or more | 30 or higher | Obese |

It is important to remember that although BMI correlates with the amount of body fat, BMI does not directly measure body fat. As a result, some people, such as athletes, may have a BMI that identifies them as overweight even though they do not have excess body fat. For more information about BMI, visit Body Mass Index.

Other methods of estimating body fat and body fat distribution include measurements of skinfold thickness and waist circumference, calculation of waist-to-hip circumference ratios, and techniques such as ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Fat Free Versus Calorie

A calorie is a calorie is a calorie whether it comes from fat or carbohydrate. Anything eaten in excess can lead to weight gain. You can lose weight by eating less calories and by increasing your physical activity. Reducing the amount of fat and saturated fat that you eat is one easy way to limit your overall calorie intake. However, eating fat-free or reduced-fat foods isn't always the answer to weight loss. This is especially true when you eat more of the reduced fat food than you would of the regular item. For example, if you eat twice as many fat-free cookies you have actually increased your overall calorie intake. The following list of foods and their reduced fat varieties will show you that just because a product is fat-free, it doesn't mean that it is "calorie-free." And, calories do count!

| Fat-Free or Reduced-Fat | Regular | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nutrient data taken from Nutrient Data System for Research, Version v4.02/30, Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota.

CDC- Calories and Weight Loss

If you are maintaining your current body weight, you are in caloric balance. If you need to gain weight or to lose weight, you'll need to tip the balance scale in one direction or another to achieve your goal.

If you need to tip the balance scale in the direction of losing weight, keep in mind that it takes approximately 3,500 calories below your calorie needs to lose a pound of body fat.1 To lose about 1 to 2 pounds per week, you'll need to reduce your caloric intake by 500—1000 calories per day.2

To learn how many calories you are currently eating, begin writing down the foods you eat and the beverages you drink each day. By writing down what you eat and drink, you become more aware of everything you are putting in your mouth. Also, begin writing down the physical activity you do each day and the length of time you do it. Here are simple paper and pencil tools to assist you:

- Food Diary (PDF-33k)

- Physical Activity Diary (PDF-42k)

An interactive version is found at My Pyramid Tracker.gov, where you can enter the foods you have eaten and the physical activity you have done to see how your calorie intake compares to your calorie expenditure. This tool requires you to register, simply to save the information you are tracking.

By studying your food diary you can be more aware of your eating habits and the number of calories you take in on an average day. Check out MyPyramid Plan to see how that number compares to the suggested food pattern for someone of your gender, age and activity level.

Physical activities (both daily activities and exercise) help tip the balance scale by increasing the calories you expend each day.

Recommended Physical Activity Levels

-

2 hours and 30 minutes (150 minutes) of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (i.e., brisk walking) every week and muscle-strengthening activities on 2 or more days a week that work all major muscle groups (legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms).

- Increasing the intensity or the amount of time that you are physically active can have even greater health benefits and may be needed to control body weight.

- Encourage children and teenagers to be physically active for at least 60 minutes each day, or almost every day.

- For more detail, see How much physical activity do you need?

The bottom line is… each person's body is unique and may have different caloric needs. A healthy lifestyle requires balance, in the foods you eat, in the beverages you consume, in the way you carry out your daily activities, and in the amount of physical activity or exercise you include in your daily routine. While counting calories is not necessary, it may help you in the beginning to gain an awareness of your eating habits as you strive to achieve energy balance. The ultimate test of balance is whether or not you are gaining, maintaining, or losing weight.

CDC:The Caloric Balance Equation

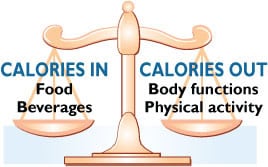

When it comes to maintaining a healthy weight for a lifetime, the bottom line is – calories count! Weight management is all about balance—balancing the number of calories you consume with the number of calories your body uses or "burns off."

- A calorie is defined as a unit of energy supplied by food. A calorie is a calorie regardless of its source. Whether you're eating carbohydrates, fats, sugars, or proteins, all of them contain calories.

- Caloric balance is like a scale. To remain in balance and maintain your body weight, the calories consumed (from foods) must be balanced by the calories used (in normal body functions, daily activities, and exercise).

| If you are... | Your caloric balance status is... |

|---|---|

| Maintaining your weight | "in balance." You are eating roughly the same number of calories that your body is using. Your weight will remain stable. |

| Gaining weight | "in caloric excess." You are eating more calories than your body is using. You will store these extra calories as fat and you'll gain weight. |

| Losing weight | "in caloric deficit." You are eating fewer calories than you are using. Your body is pulling from its fat storage cells for energy, so your weight is decreasing. |

ADA: Diabetes

Diabetes and Metabolic Health

People with diabetes are more likely to be overweight and to have high blood pressure and high cholesterol. At least one out of every five overweight people has several metabolic problems at once, which can lead to serious complications like heart disease.

Are You at Risk for Obesity?

One way to find out if your weight puts you at risk for diabetes is to look at your body mass index, or BMI, which is based on a calculation of your height and weight. Use our BMI calculator to find out.

Getting Motivated

Getting motivated to lose weight can be hard, especially if you have tried to lose weight in the past. Find out whether you are ready to begin a weight loss plan and get inspired to take the first step.

Getting Started

Learn what you can do to lower your risk.

Small Steps for Your Health

Changing to a healthier lifestyle can be tough. Get ideas and tips for making small steps towards a healthier lifestyle. Also, find out what the ingredients are for success.

Healthy Weight Loss

Reality is that losing weight in a healthy way and learning how to to keep it off for years is not easy. It takes a new way of thinking. Are you ready?

Be Active! But How?

Being active is a big part of living a healthy lifestyle. Check out the benefits of being active, how much activity is best for you, and get a few tips to be more active now.

Weight Loss Matters Tip Sheets

Our tip sheets will give you ideas on how you can get started losing weight by exercising and eating healthy. These sheets will help you get motivated, make changes, and stick to those changes.

Types of diabetes- CDC

Type 1 diabetes was previously called insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) or juvenile-onset diabetes. Type 1 diabetes develops when the body's immune system destroys pancreatic beta cells, the only cells in the body that make the hormone insulin that regulates blood glucose. To survive, people with type 1 diabetes must have insulin delivered by injection or a pump. This form of diabetes usually strikes children and young adults, although disease onset can occur at any age. In adults, type 1 diabetes accounts for 5% to 10% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes. Risk factors for type 1 diabetes may be autoimmune, genetic, or environmental. There is no known way to prevent type 1 diabetes. Several clinical trials for preventing type 1 diabetes are currently in progress or are being planned.

Type 2 diabetes was previously called non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) or adult-onset diabetes. In adults, type 2 diabetes accounts for about 90% to 95% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes. It usually begins as insulin resistance, a disorder in which the cells do not use insulin properly. As the need for insulin rises, the pancreas gradually loses its ability to produce it. Type 2 diabetes is associated with older age, obesity, family history of diabetes, history of gestational diabetes, impaired glucose metabolism, physical inactivity, and race/ethnicity. African Americans, Hispanic/Latino Americans, American Indians, and some Asian Americans and Native Hawaiians or Other Pacific Islanders are at particularly high risk for type 2 diabetes and its complications. Type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents, although still rare, is being diagnosed more frequently among American Indians, African Americans, Hispanic/Latino Americans, and Asians/Pacific Islanders.

Gestational diabetes is a form of glucose intolerance diagnosed during pregnancy. Gestational diabetes occurs more frequently among African Americans, Hispanic/Latino Americans, and American Indians. It is also more common among obese women and women with a family history of diabetes. During pregnancy, gestational diabetes requires treatment to normalize maternal blood glucose levels to avoid complications in the infant. Immediately after pregnancy, 5% to 10% of women with gestational diabetes are found to have diabetes, usually type 2. Women who have had gestational diabetes have a 40% to 60% chance of developing diabetes in the next 5–10 years.

Other types of diabetes result from specific genetic conditions (such as maturity-onset diabetes of youth), surgery, medications, infections, pancreatic disease, and other illnesses. Such types of diabetes account for 1% to 5% of all diagnosed cases.

Health Risks of Overweight and Obesity

Being overweight or obese isn’t a cosmetic problem. It greatly raises the risk in adults for many diseases and conditions.

Overweight and Obesity-Related Health Problems in Adults

Heart Disease

This condition occurs when a fatty material called plaque (plak) builds up on the inside walls of the coronary arteries (the arteries that supply blood and oxygen to your heart). Plaque narrows the coronary arteries, which reduces blood flow to your heart. Your chances for having heart disease and a heart attack get higher as your body mass index (BMI) increases. Obesity also can lead to congestive heart failure, a serious condition in which the heart can’t pump enough blood to meet your body’s needs.

High Blood Pressure (Hypertension)

This condition occurs when the force of the blood pushing against the walls of the arteries is too high. Your chances for having high blood pressure are greater if you’re overweight or obese.

Stroke

Being overweight or obese can lead to a buildup of fatty deposits in your arteries that form a blood clot. If the clot is close to your brain, it can block the flow of blood and oxygen and cause a stroke. The risk of having a stroke rises as BMI increases.

Type 2 Diabetes

This is a disease in which blood sugar (glucose) levels are too high. Normally, the body makes insulin to move the blood sugar into cells where it’s used. In type 2 diabetes, the cells don’t respond enough to the insulin that’s made. Diabetes is a leading cause of early death, heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, and blindness. More than 80 percent of people with type 2 diabetes are overweight.

Abnormal Blood Fats

If you’re overweight or obese, you have a greater chance of having abnormal levels of blood fats. These include high amounts of triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (a fat-like substance often called “bad” cholesterol), and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (often called “good” cholesterol). Abnormal levels of these blood fats are a risk for heart disease.

Metabolic Syndrome

This is the name for a group of risk factors linked to overweight and obesity that raise your chance for heart disease and other health problems such as diabetes and stroke. A person can develop any one of these risk factors by itself, but they tend to occur together. Metabolic syndrome occurs when a person has at least three of these heart disease risk factors:

- A large waistline. This is also called abdominal obesity or “having an apple shape.” Having extra fat in the waist area is a greater risk factor for heart disease than having extra fat in other parts of the body, such as on the hips.

- Abnormal blood fat levels, including high triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol.

- Higher than normal blood pressure.

- Higher than normal fasting blood sugar levels.

Cancer

Being overweight or obese raises the risk for colon, breast, endometrial, and gallbladder cancers.

Osteoarthritis

This is a common joint problem of the knees, hips, and lower back. It occurs when the tissue that protects the joints wears away. Extra weight can put more pressure and wear on joints, causing pain.

Sleep Apnea

This condition causes a person to stop breathing for short periods during sleep. A person with sleep apnea may have more fat stored around the neck. This can make the breathing airway smaller so that it’s hard to breathe.

Reproductive Problems

Obesity can cause menstrual irregularity and infertility in women.

Gallstones

These are hard pieces of stone-like material that form in the gallbladder. They’re mostly made of cholesterol and can cause abdominal or back pain. People who are overweight or obese have a greater chance of having gallstones. Also, being overweight may result in an enlarged gallbladder that may not work properly.

Overweight and Obesity-Related Health Problems in Children and Teens

Overweight and obesity also increase the health risks for children and teens. Type 2 diabetes was once rare in American children. Now it accounts for 8 to 45 percent of newly diagnosed diabetes cases. Also, overweight children are more likely to become overweight or obese as adults, with the same risks for disease.

nih

What do moderate- and vigorous-intensity mean?

Moderate: While performing the physical activity, if your breathing and heart rate is noticeably faster but you can still carry on a conversation — it's probably moderately intense. Examples include—

- Walking briskly (a 15-minute mile).

- Light yard work (raking/bagging leaves or using a lawn mower).

- Light snow shoveling.

- Actively playing with children.

- Biking at a casual pace.

Vigorous: Your heart rate is increased substantially and you are breathing too hard and fast to have a conversation, it's probably vigorously intense. Examples include—

- Jogging/running.

- Swimming laps.

- Rollerblading/inline skating at a brisk pace.

- Cross-country skiing.

- Most competitive sports (football, basketball, or soccer).

- Jumping rope.

The following table shows calories used in common physical activities at both moderate and vigorous levels.

| Calories Used per Hour in Common Physical Activities | ||

|---|---|---|

| Moderate Physical Activity | Approximate Calories/30 Minutes for a 154 lb Person1 | Approximate Calories/Hr for a 154 lb Person1 |

| Hiking | 185 | 370 |

| Light gardening/yard work | 165 | 330 |

| Dancing | 165 | 330 |

| Golf (walking and carrying clubs) | 165 | 330 |

| Bicycling (<10> | 145 | 290 |

| Walking (3.5 mph) | 140 | 280 |

| Weight lifting (general light workout) | 110 | 220 |

| Stretching | 90 | 180 |

| Vigorous Physical Activity | Approximate Calories/30 Minutes for a 154 lb Person1 | Approximate Calories/Hr for a 154 lb Person1 |

| Running/jogging (5 mph) | 295 | 590 |

| Bicycling (>10 mph) | 295 | 590 |

| Swimming (slow freestyle laps) | 255 | 510 |

| Aerobics | 240 | 480 |

| Walking (4.5 mph) | 230 | 460 |

| Heavy yard work (chopping wood) | 220 | 440 |

| Weight lifting (vigorous effort) | 220 | 440 |

| Basketball (vigorous) | 220 | 440 |

| 1Calories burned per hour will be higher for persons who weigh more than 154 lbs (70 kg) and lower for persons who weigh less. Source: Adapted from Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005, page 16, Table 4. | ||

To help estimate the intensity of your physical activity, see Physical Activity for Everyone: Measuring Physical Activity Intensity.

cdcGet Moving!

In addition to a healthy eating plan, an active lifestyle will help you maintain your weight. By choosing to add more physical activity to your day, you'll increase the amount of calories your body burns. This makes it more likely you'll maintain your weight.

Although physical activity is an integral part of weight management, it's also a vital part of health in general. Regular physical activity can reduce your risk for many chronic diseases and it can help keep your body healthy and strong.

Regular physical activity is important for good health, and it's especially important if you're trying to lose weight or to maintain a healthy weight.

- When losing weight, more physical activity increases the number of calories your body uses for energy or "burns off." The burning of calories through physical activity, combined with reducing the number of calories you eat, creates a "calorie deficit" that results in weight loss.

- Most weight loss occurs because of decreased caloric intake. However, evidence shows the only way to maintain weight loss is to be engaged in regular physical activity.

- Most importantly, physical activity reduces risks of cardiovascular disease and diabetes beyond that produced by weight reduction alone.

Physical activity also helps to–

- Maintain weight.

- Reduce high blood pressure.

- Reduce risk for type 2 diabetes, heart attack, stroke, and several forms of cancer.

- Reduce arthritis pain and associated disability.

- Reduce risk for osteoporosis and falls.

- Reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety.

When it comes to weight management, people vary greatly in how much physical activity they need. Here are some guidelines to follow:

To maintain your weight: Work your way up to 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, or an equivalent mix of the two each week. Strong scientific evidence shows that physical activity can help you maintain your weight over time. However, the exact amount of physical activity needed to do this is not clear since it varies greatly from person to person. It's possible that you may need to do more than the equivalent of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity a week to maintain your weight.

To lose weight and keep it off: You will need a high amount of physical activity unless you also adjust your diet and reduce the amount of calories you're eating and drinking. Getting to and staying at a healthy weight requires both regular physical activitycdc

The National Weight Control Registry

How to Join

Recruitment for the Registry is ongoing. If you are at least 18 years of age and have maintained at least a 30 pound weight loss for one year or longer you may be eligible to join our research study.

For Current Registry Members

Have you relocated over the past year? Please update your contact info here.

Research Findings

Learn more about our research. To date, we have published articles describing the eating and exercise habits of successful weight losers, the behavioral strategies they use to maintain their weight, and the effect of successful weight loss maintenance on other areas of their lives.

Success Stories

Registry members' weight loss stories are diverse and inspiring. Read about the accomplishments of some of our members.

Who We Are

Read about the developers, co-investigators and research staff of the NWCR team.

Media Requests

Looking to feature the NWCR in your article or story? Contact us for more information.

Learn more about the sub-studies of the Registry.

The National Weight Control Registry (NWCR), established in 1994 by Research findings from the National Weight Control Registry have been featured in many national newspapers, magazines, and television broadcasts, including USA Today, Oprah magazine, The Washington Post, and Good Morning America. |

Are you a successful loser? |

Find out more: Please contact us with any questions or comments.

PLEASE NOTE: The National Weight Control Registry is NOT a weight loss treatment program and we are unable to respond to requests for general information on weight loss and maintenance. |

healthy weight loss

It's natural for anyone trying to lose weight to want to lose it very quickly. But evidence shows that people who lose weight gradually and steadily (about 1 to 2 pounds per week) are more successful at keeping weight off. Healthy weight loss isn't just about a "diet" or "program". It's about an ongoing lifestyle that includes long-term changes in daily eating and exercise habits.

To lose weight, you must use up more calories than you take in. Since one pound equals 3,500 calories, you need to reduce your caloric intake by 500—1000 calories per day to lose about 1 to 2 pounds per week.1

Once you've achieved a healthy weight, by relying on healthful eating and physical activity most days of the week (about 60—90 minutes, moderate intensity), you are more likely to be successful at keeping the weight off over the long term.

Losing weight is not easy, and it takes commitment. But if you're ready to get started, we've got a step-by-step guide to help get you on the road to weight loss and better health.

Even Modest Weight Loss Can Mean Big Benefits

The good news is that no matter what your weight loss goal is, even a modest weight loss, such as 5 to 10 percent of your total body weight, is likely to produce health benefits, such as improvements in blood pressure, blood cholesterol, and blood sugars.2

For example, if you weigh 200 pounds, a 5 percent weight loss equals 10 pounds, bringing your weight down to 190 pounds. While this weight may still be in the "overweight" or "obese" range, this modest weight loss can decrease your risk factors for chronic diseases related to obesity.

So even if the overall goal seems large, see it as a journey rather than just a final destination. You'll learn new eating and physical activity habits that will help you live a healthier lifestyle. These habits may help you maintain your weight loss over time.

In addition to improving your health, maintaining a weight loss is likely to improve your life in other ways. For example, a study of participants in the National Weight Control Registry* found that those who had maintained a significant weight loss reported improvements in not only their physical health, but also their energy levels, physical mobility, general mood, and self-confidence.

cdc

Prediabetes?

Progression to diabetes among those with prediabetes is not inevitable. Studies suggest that weight loss and increased physical activity among people with prediabetes prevent or delay diabetes and may return blood glucose levels to normal.

From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Prediabetes: Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose

Prediabetes is a condition in which individuals have blood glucose levels higher than normal but not high enough to be classified as diabetes. People with prediabetes have an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke.

- People with prediabetes have impaired fasting glucose (IFG) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT). Some people have both IFG and IGT.

- IFG is a condition in which the fasting blood sugar level is 100 to 125 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) after an overnight fast. This level is higher than normal but not high enough to be classified as diabetes.

- IGT is a condition in which the blood sugar level is 140 to 199 mg/dL after a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test. This level is higher than normal but not high enough to be classified as diabetes.

- In 1988–1994, among U.S. adults aged 40–74 years, 33.8% had IFG, 15.4% had IGT, and 40.1% had prediabetes (IGT or IFG or both). More recent data for IFG, but not IGT, are available and are presented below.

Prevalence of impaired fasting glucose in people younger than 20 years of age, United States, 2007

- In 1999–2000, 7.0% of U.S. adolescents aged 12–19 years had IFG.

Prevalence of impaired fasting glucose in people aged 20 years or older, United States, 2007

- In 2003–2006, 25.9% of U.S. adults aged 20 years or older had IFG (35.4% of adults aged 60 years or older). Applying this percentage to the entire U.S. population in 2007 yields an estimated 57 million American adults aged 20 years or older with IFG, suggesting that at least 57 million American adults had prediabetes in 2007.

- After adjusting for population age and sex differences, IFG prevalence among U.S. adults aged 20 years or older in 2003–2006 was 21.1% for non-Hispanic blacks, 25.1% for non-Hispanic whites, and 26.1% for Mexican Americans.

Prevention or delay of diabetes

- Progression to diabetes among those with prediabetes is not inevitable. Studies have shown that people with prediabetes who lose weight and increase their physical activity can prevent or delay diabetes and return their blood glucose levels to normal.

- The Diabetes Prevention Program, a large prevention study of people at high risk for diabetes, showed that lifestyle intervention reduced developing diabetes by 58% during a 3-year period. The reduction was even greater, 71%, among adults aged 60 years or older.

- Interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in individuals with prediabetes can be feasible and cost-effective. Research has found that lifestyle interventions are more cost-effective than medications.

Calculation of BMI

BMI is calculated the same way for both adults and children. The calculation is based on the following formulas:

| Measurement Units | Formula and Calculation |

|---|---|

| Kilograms and meters (or centimeters) | Formula: weight (kg) / [height (m)]2 With the metric system, the formula for BMI is weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Since height is commonly measured in centimeters, divide height in centimeters by 100 to obtain height in meters. Example: Weight = 68 kg, Height = 165 cm (1.65 m) |

| Pounds and inches | Formula: weight (lb) / [height (in)]2 x 703 Calculate BMI by dividing weight in pounds (lbs) by height in inches (in) squared and multiplying by a conversion factor of 703. Example: Weight = 150 lbs, Height = 5'5" (65") |

Interpretation of BMI for adults

For adults 20 years old and older, BMI is interpreted using standard weight status categories that are the same for all ages and for both men and women. For children and teens, on the other hand, the interpretation of BMI is both age- and sex-specific. For more information about interpretation for children and teens, visit Child and Teen BMI Calculator.

The standard weight status categories associated with BMI ranges for adults are shown in the following table.

BMI | Weight Status |

|---|---|

| Below 18.5 | Underweight |

| 18.5 – 24.9 | Normal |

| 25.0 – 29.9 | Overweight |

| 30.0 and Above | Obese |

For example, here are the weight ranges, the corresponding BMI ranges, and the weight status categories for a sample height.

| Height | Weight Range | BMI | Weight Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5' 9" | 124 lbs or less | Below 18.5 | Underweight |

| 125 lbs to 168 lbs | 18.5 to 24.9 | Normal | |

| 169 lbs to 202 lbs | 25.0 to 29.9 | Overweight | |

| 203 lbs or more | 30 or higher | Obese |

How reliable is BMI as an indicator of body fatness?

The correlation between the BMI number and body fatness is fairly strong; however the correlation varies by sex, race, and age. These variations include the following examples: 3, 4

- At the same BMI, women tend to have more body fat than men.

- At the same BMI, older people, on average, tend to have more body fat than younger adults.

- Highly trained athletes may have a high BMI because of increased muscularity rather than increased body fatness.

It is also important to remember that BMI is only one factor related to risk for disease. For assessing someone's likelihood of developing overweight- or obesity-related diseases, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines recommend looking at two other predictors:

- The individual's waist circumference (because abdominal fat is a predictor of risk for obesity-related diseases).

- Other risk factors the individual has for diseases and conditions associated with obesity (for example, high blood pressure or physical inactivity).

For more information about the assessment of health risk for developing overweight- and obesity-related diseases, visit the following Web pages from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute:

- Assessing Your Risk

- Body Mass Index Table

- Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults

If an athlete or other person with a lot of muscle has a BMI over 25, is that person still considered to be overweight?

According to the BMI weight status categories, anyone with a BMI over 25 would be classified as overweight and anyone with a BMI over 30 would be classified as obese.

It is important to remember, however, that BMI is not a direct measure of body fatness and that BMI is calculated from an individual's weight which includes both muscle and fat. As a result, some individuals may have a high BMI but not have a high percentage of body fat. For example, highly trained athletes may have a high BMI because of increased muscularity rather than increased body fatness. Although some people with a BMI in the overweight range (from 25.0 to 29.9) may not have excess body fatness, most people with a BMI in the obese range (equal to or greater than 30) will have increased levels of body fatness.

It is also important to remember that weight is only one factor related to risk for disease. If you have questions or concerns about the appropriateness of your weight, you should discuss them with your healthcare provider.

What are the health consequences of overweight and obesity for adults?

The BMI ranges are based on the relationship between body weight and disease and death.5 Overweight and obese individuals are at increased risk for many diseases and health conditions, including the following: 6

- Hypertension

- Dyslipidemia (for example, high LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, or high levels of triglycerides)

- Type 2 diabetes

- Coronary heart disease

- Stroke

- Gallbladder disease

- Osteoarthritis

- Sleep apnea and respiratory problems

- Some cancers (endometrial, breast, and colon)

For more information about these and other health problems associated with overweight and obesity, visit Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults.

Is BMI interpreted the same way for children and teens as it is for adults?

Although the BMI number is calculated the same way for children and adults, the criteria used to interpret the meaning of the BMI number for children and teens are different from those used for adults. For children and teens, BMI age- and sex-specific percentiles are used for two reasons:

- The amount of body fat changes with age.

- The amount of body fat differs between girls and boys.

Because of these factors, the interpretation of BMI is both age- and sex-specific for children and teens. The CDC BMI-for-age growth charts take into account these differences and allow translation of a BMI number into a percentile for a child's sex and age.

For adults, on the other hand, BMI is interpreted through categories that are not dependent on sex or age.

cdc

Remove calorie-rich temptations!

Remove calorie-rich temptations!

Cold, Flu, Sinus, and Allergy

Cold, Flu, Sinus, and Allergy Diabetes

Diabetes Digestive System

Digestive System Pain & Arthritis

Pain & Arthritis Vitamin Guide

Vitamin Guide Herbal Remedies

Herbal Remedies Homeopathy

Homeopathy Weight Management

Weight Management Sports Nutrition

Sports Nutrition Women's Health

Women's Health Men's Health

Men's Health